For decades, research in distributed systems, particularly Byzantine consensus and state machine replication (SMR), has focused on two main goals: consistency and availability. Consistency means that all nodes agree on the same set of transactions, while liveness ensures that the system keeps adding new transactions. Still, these properties do not prevent a malicious party from changing the order of transactions after they are received.

In public blockchains, gaps in traditional consensus guarantees are a serious problem. Validators, block builders, or sequencers can exploit their privileged role in block ordering for financial gain, an act known as Maximum Extractable Value (MEV). This operation involves a profitable front-running, back-running, and transactional sandwich. The order in which transactions are executed determines the effectiveness and profitability of DeFi applications, so consistent transaction order is essential to maintain fairness and trust.

To address this critical security gap, transaction order fairness is proposed as a third important consensus property. Fair ordering protocols ensure that the final order of transactions depends on external objective factors such as arrival time (or order of receipt) and is resistant to adversarial reordering. These protocols bring blockchains closer to transparency, predictability, and MEV resistance by limiting the power that block proposers have to change the order of transactions.

Condorcet’s paradox and the impossibility of ideal fairness

The most intuitive and most powerful fairness concept is receive order fairness (ROF). Informally defined as “first to receive, first to output”, ROF requires that if there are enough transactions, (TX) Arrives at most nodes earlier than another transaction (tx’)then the system should order TX in front tx’ for execution.

However, achieving this widely accepted “ordering fairness” is fundamentally impossible unless we assume that all nodes can communicate instantaneously (i.e., work with an external network that synchronizes instantaneously). This impossible result arises from a surprising connection to social choice theory, specifically the Condorcet paradox.

The Condorcet paradox shows that even if all individual nodes maintain a transitive internal order of transactions, system-wide collective priorities can result in so-called intransitive cycles. For example, a majority of nodes may receive the transaction. a in front Bthe majority receives B in front Cthe majority receive C in front a. Therefore, the three majority preferences form a loop (a→B→C→a). This means that no single consistent ordering of transactions A, B, and C can simultaneously satisfy all majority priorities.

This paradox illustrates why the goal of achieving complete reception order fairness is not possible in asynchronous networks. Also, even synchronous networks that share a common clock are not possible if the external network has too long a delay. This impossibility necessitates adopting a weaker definition of fairness, such as batch order fairness.

Hedera hashgraph and median timestamp flaws

Hedera employs a hashgraph consensus algorithm and attempts to approximate the powerful concept of receiving order fairness (ROF). This is done by assigning each transaction a final timestamp that is calculated as the median of the local timestamps of all nodes in that transaction.

However, this is inherently susceptible to manipulation. A single adversarial node can intentionally distort local timestamps and reverse the final order of two transactions, even if all honest participants received the transactions in the correct order.

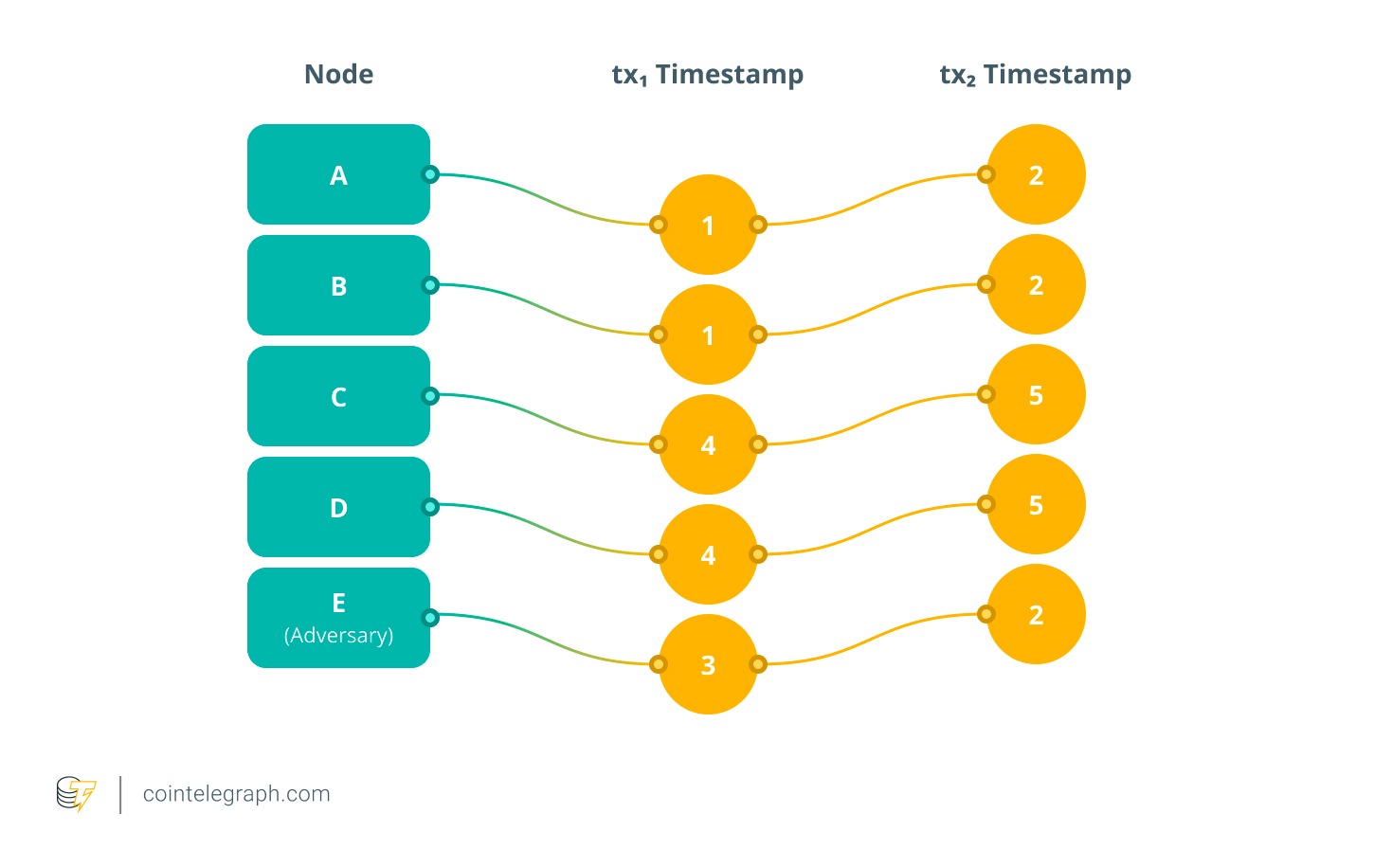

Consider a simple example with five consensus nodes (A, B, C, D, and E) where node E behaves maliciously. Two transactions tx1 and tx2 are broadcast to the network. Since all honest nodes receive tx₁ before tx₂, the expected final order should be tx₁ → tx₂.

In this example, the attacker assigns tx1 a later timestamp (3) and tx2 an earlier timestamp (2) to skew the median.

When the protocol calculates the median:

-

For tx1, the median of timestamps (1, 1, 4, 4, 3) is 3.

-

For tx2, the median of timestamps (2, 2, 5, 5, 2) is 2.

Since the final timestamp of tx1 (3) is greater than the timestamp of tx2 (2), the protocol outputs tx2 → tx1, reversing the true order observed by all honest nodes.

This toy example shows serious flaws. Although the median function appears neutral, it is paradoxically the actual source of inequity. This is because even a single rogue participant can exploit it to bias the final trading order.

As a result, the “fair timestamp” that Hashgraph so often touts is a surprisingly weak concept of fairness. Hashgraph consensus cannot guarantee the fairness of incoming orders and instead relies on a set of authorized validators rather than cryptographic guarantees.

Delivering substantial guarantees

However, to avoid the theoretical impossibility demonstrated by Condorcet, a real fair ordering scheme must somehow relax the definition of fairness.

The Aequitas protocol introduced a criterion for block order fairness (BOF), or batch order fairness. BOF specifies that if a sufficient number of nodes receive a transaction tx before another transaction tx’, then tx must be delivered in a block before or at the same time as tx’. That is, an honest node cannot deliver tx’ in the block after tx. This relaxes the rule from “must be delivered before” (a requirement of ROF) to “must be delivered at the latest”.

Consider three consensus nodes (A, B, C) and three transactions (tx₁, tx₂, and tx₃). A transaction is considered “earlier received” if at least two (majority) of the three nodes observe the transaction first.

Applying majority voting to determine the global order results in:

-

tx₁ → tx₂ (Agreement between A and C)

-

tx₂ → tx₃ (agreement between A and B)

-

tx₃ → tx₁ (Agreement between B and C)

These settings create a loop: tx₁ → tx₂ → tx₃ → tx₁. In this situation, there is no single instruction that can satisfy everyone’s opinion at once, meaning that achieving a strict ROF is impossible.

BOF solves this problem by grouping all conflicting transactions into the same batch or block instead of forcing them to come before each other. The protocol simply prints:

Block B₁ = {tx₁, tx₂, tx₃}

This means that from a protocol perspective, all three transactions are treated as if they occurred at the same time. Within a block, a deterministic tiebreaker (such as a hash value) determines the exact order in which things are executed. This allows BOF to ensure the fairness of all pairs of transactions and keep the final transaction log consistent for everyone. Each operation is processed up to and including the one before it.

This small but important adjustment allows the protocol to handle situations with conflicting transaction orders by grouping conflicting transactions into the same block or batch. Importantly, this does not result in partial ordering, as all nodes must agree on one single linear transaction sequence. Transactions within each block are arranged in a fixed order for execution. Even when such conflicts do not occur, the protocol achieves stronger ROF characteristics.

Although Aequitas was successful in achieving BOF, it faced significant limitations, especially the very high communication complexity that could only guarantee weak survivability. Weak survivability means that the delivery of a transaction is guaranteed only after the entire Condorcet cycle of which it is a part is completed. This can take a very long time if the cycles are “chained”.

The Themis protocol was introduced to enforce the same strong BOF properties, but with improved communication complexity. Themis accomplishes this using three techniques: batch unspooling, lazy ordering, and stronger within-batch guarantees.

In its standard form, Themis requires each participant to exchange messages with most other nodes in the network. The amount of communication required increases with the square of the number of network participants. However, in its optimized version, SNARK-Themis, nodes do not need to communicate directly with all other participants and use concise cryptographic proofs to verify fairness. This reduces the communication load and increases only linearly, allowing Themis to scale efficiently even in large networks.

Assume that five nodes (A to E) participating in consensus receive three transactions (tx₁, tx₂, and tx₃). Local ordering will vary due to network delays.

Similar to Aequitas, these preferences form the Condorcet cycle. However, instead of waiting for the entire cycle to resolve, Themis uses a method called batch unspooling to keep the system running. It identifies all transactions that are part of a cycle and groups them into one set called strongly connected components (SCCs). In this case, all three transactions belong to the same SCC, and Themis prints it as an in-progress batch and labels it Batch B₁ = {tx₁, tx₂, tx₃}.

This allows Themis to allow the network to continue processing new transactions even while internal orders for batch B₁ are still being finalized. This keeps the system up and running and avoids outages.

overview:

The concept of perfect fairness in transaction ordering may seem simple. The transaction of the first person to reach the network must be processed first. However, as the Condorcet paradox shows, this ideal does not hold true in real distributed systems. Different nodes see transactions in different orders, and if their views conflict, no protocol can construct a single, universally “correct” sequence without compromise.

Hedera’s hashgraph attempts to approximate this ideal using median timestamps, but that approach relies more on trust than evidence. One rogue participant can skew the median and reverse the transaction order, revealing that “fair timestamps” are not truly fair.

Protocols such as Aequitas and Themis move the discussion forward by recognizing what can and cannot be achieved. Rather than pursuing the impossible, we redefine fairness in a way that maintains ordering consistency even under real-world network conditions. What emerges is not a rejection of fairness, but its evolution. This evolution draws a clear line between perceived and provable fairness. This shows that true transaction order integrity in a decentralized system cannot depend on reputation, validator trust, or granted control. This must be obtained from cryptographic validation built into the protocol itself.

This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk and readers should conduct their own research when making decisions.

This article is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to be, and should not be taken as, legal or investment advice. The views, ideas, and opinions expressed herein are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.

Cointelegraph does not endorse the content of this article or the products mentioned here. Readers should do their own research before taking any action related to the products or companies mentioned and are solely responsible for their decisions.